Vindan’s fictions

Stories that govern our world

There is no denying that the Israeli historian Yuval Noah Harari is a controversial academic, and yet, I was very upset at how short his discussion on the concept of ‘fictions’ was in his books, and at the fact that he has not written a separate book on just this subject. Harari’s fictions are abstractions that are created and shared in the collective imagination of a society, organisation, country, or sometimes even the entirety of humankind. This includes all human creations that are not tangible, objective, and physical realities—religions, countries, corporations, laws, morals, norms, the economy, et cetera. Other animals are concerned only with describing to each other the truth, that is, either there is a tiger behind the bushes, or there is not, and the herd should conduct itself accordingly. While humans too are very concerned with the presence or lack thereof of the actual tiger, they are even more engaged with imagined, shared realities—Harari’s fictions—which, in prehistory, allowed them to consolidate their power at an unprecedented level. With behavioural modernity came proto-religions, which developed into such profoundly unifying social systems that they allowed humans to effectively bypass the supposed Dunbar’s limit of 150 individuals per tribe and establish confederal supertribes, and eventually, to completely dominate all other animals of the Earth, including even the other homo primates.

If you have watched the Spanish heist drama La Casa de Papel on television, then I have no better illustration for Harari’s fictions than the setup of Part 5 of the show (spoilers): The Professor’s gang of bank robbers wants to extract all of the gold from the Spanish national reserve at the Bank of Spain, but when cornered into a Mexican standoff by security forces toward the end of the operation, they end up cutting a deal not to return the gold, but instead to replace the gold with gold-covered brass, in exchange for immunity and new identities for the gang members, just so that the Spanish state can pretend that it has recovered its national reserve. Regardless of the plausibility of this in real life, why does this at least work in the show? Quite obviously, modern countries use fiat currencies (like the US dollar) to conduct trade and settle debts, and state-held gold is ostensibly never used for any direct transactions. Since the gold standard has fallen into disuse, gold reserves today exist mostly as phantasms to preserve the perceived stability of the economy, the confidence of investors, and the creditworthiness of the state. According to La Casa de Papel, they are “an illusion,” “useless,” and “merely psychological”. As long as everybody believes that a country has a substantial gold reserve, it does not matter whether, in actual, physical reality, its central bank is filled with real gold or shiny brass. Therefore, the Spanish gold reserve is but a fiction that exists in our collective imagination. One of the best lines of dialogue in La Casa de Papel, in my opinion, is in Part 2, when the Professor tears up banknotes in front of the ex-policewoman Raquel Murillo, saying, “What’s this? This is nothing, Raquel. Paper. It’s paper, you see?”

Our modern lives as humans are completely defined by fictions. Virtually everything we do, make, or believe in is tied to these imagined constructs. Even though money is indeed just “paper,” it holds value because billions of people agree that it does, and because it affords us such real things as groceries, technological innovation, and humanitarian aid. Even though universities and other research institutes are but organised groups of humans, they hold value because these humans agree to come together to seek the truth and believe that the pursuit of the truth is good. Even though countries are but a drawing of a map projected onto our planet, they hold value because many people agree that their identities, missions, and purposes are indeed derived in part from the piece of land that they belong to, and because this level of unity enables cooperation at a level so unparalleled that it landed us on the Moon.

The reason why fictions were able to make humans the masters of their planet is because they bestowed upon them the ability to allocate an extremely large amount of resources extremely efficiently. United by their shared stories, beliefs, and traditions, unlike any other animal, humans were able to exponentially increase their strength, intelligence, and social complexity as they came together, first as villages, then as cities, then as kingdoms and empires, then as nation-states, and then as corporations. The wealth that we have created and the impact that we have had on our world because of our fictions is utterly inconceivable to any other known living being. Now that we understand what Harari’s fictions are and the massive role that they play in our lives, I invite you to another discussion in which we will look at how these fictions are connected and why these connections are important.

Vindan’s fictions

‘Vindan’s fictions’ are fictions that legitimise, and are legitimised by, other fictions. A Vindanist, therefore, posits a hierarchy of fictions, of which the upper fictions—like laws, borders, corporations, and social norms—are usually those that directly govern human society, and the lower fictions—like legends, postulates, science, and constitutions—form the foundations of our constructed reality.

As an example of Vindan’s fictions, the fiction that is the international border between Turkey and Greece (an imaginary line) is legitimised by the fiction that is the Treaty of Lausanne (just paper), which is itself legitimised by the fictions that are/were the governments of the allied powers and of Republican Turkey (organised groups of humans). Similarly, going back to our discussion on La Casa de Papel, it can be said that the fiction that is modern Spain’s gold reserve helps legitimise the other fiction that is the Spanish economy.

Owing to our sheer sophistication as social animals, the hierarchies of fictions in human societies tend to be very large and highly dynamic, meaning that they can change, expand, be destroyed, and have many internal contradictions. A comprehensive study of this concept of the hierarchy of fictions, now, will enable us to understand why I am so eager to submit their many fascinating real-world potential applications later in this paper.

Hierarchy of fictions

To better understand Vindan’s hierarchy of fictions, let us consider a Country X (with its legal constitution partly based on my fictional country Ayistan). Country X is a modern democratic constitutional monarchy (like Japan or the UK), in which Ramu and Shamu are two domiciled adult citizens. One night, Ramu steals an expensive laptop from Shamu, for which he is later arrested by the police.

Ramu is convicted of theft and is sentenced to prison because of the fiction that is the rule that stealing from others is wrong.

The above fiction is legitimised in part by the fiction that is the statutory law in Country X which criminalises theft.

The above fiction is legitimised by the fiction that is the Legislature of Country X, which is itself part of the fiction that is the Government of Country X.

The above fictions are legitimised by the fiction that is the Constitution of Country X.

The above fiction is legitimised by the fiction that is the Democracy Edict, through which, around a hundred years ago, the King of Country X at the time transformed Country X from an absolute monarchy into a constitutional, democratic state (for modernisation and high social and economic freedom).

The above fiction is legitimised by the fiction that is the monarchy of Country X and by the fiction that the word of the King of Country X, transmitted and codified in the form of royal edicts, is its supreme law. However, a convention to never issue any more royal edicts developed in Country X immediately after the Democracy Edict in order to enable the practical supremacy of the Constitution, even though the monarch nominally remains the actual fount of the law.

The above fictions are legitimised by the fiction that the Kings of Country X are descended from the ‘Children of the God of Nature’, who were, according to the mythology of Country X, demigods who founded human civilisation 10,000 years ago and correctly interpreted and adopted the Laws of Nature for themselves and their progeny. This is exactly, parenthetically, why the word of the King of Country X is the law. Because the ruling dynasty of Country X has been unbroken for thousands of years and goes back to semi-legendary and undocumented figures, this fiction can be, as of yet, neither proven nor disproven by an empiricist.

The above fiction is legitimised by the fiction that is the ‘God of Nature’, who, according to the mythology of Country X, is the creator of the universe and its natural laws, and the ancestor to both his Children who founded human civilisation and the Kings who have reigned over Country X. Because it is theistic and supposedly extranatural in nature, this fiction can be, as of yet, neither proven nor disproven by an empiricist.

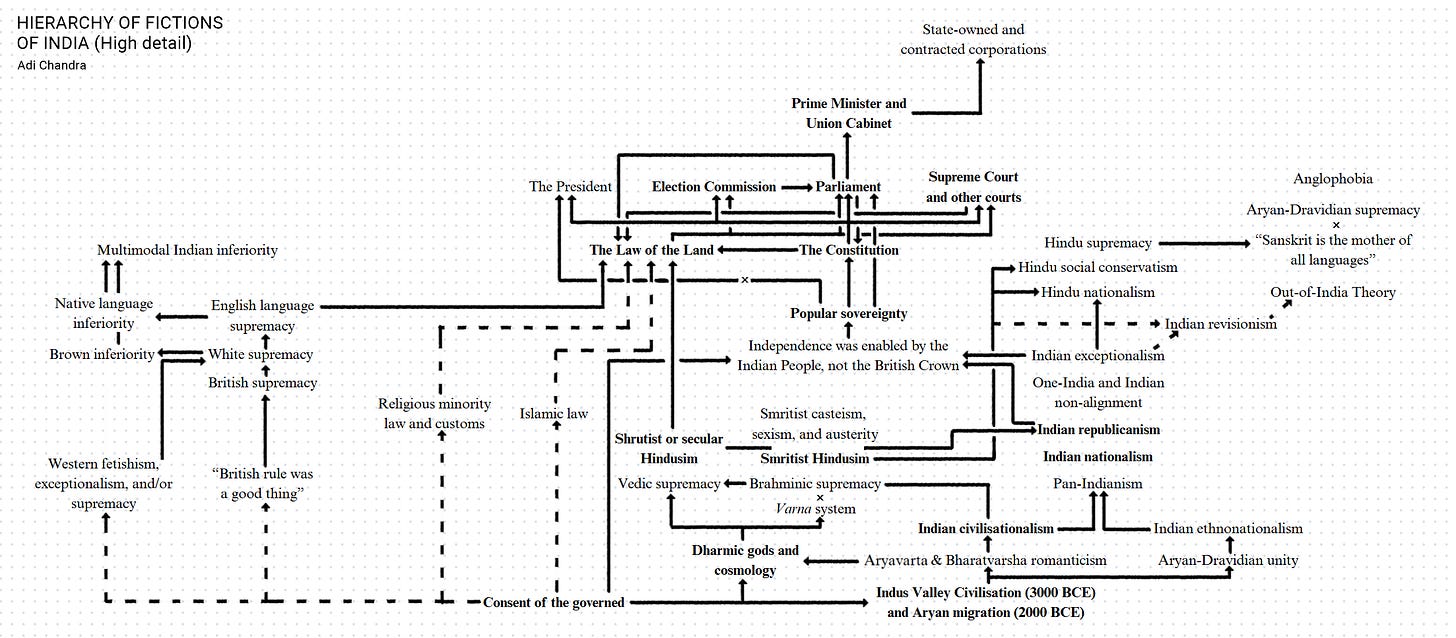

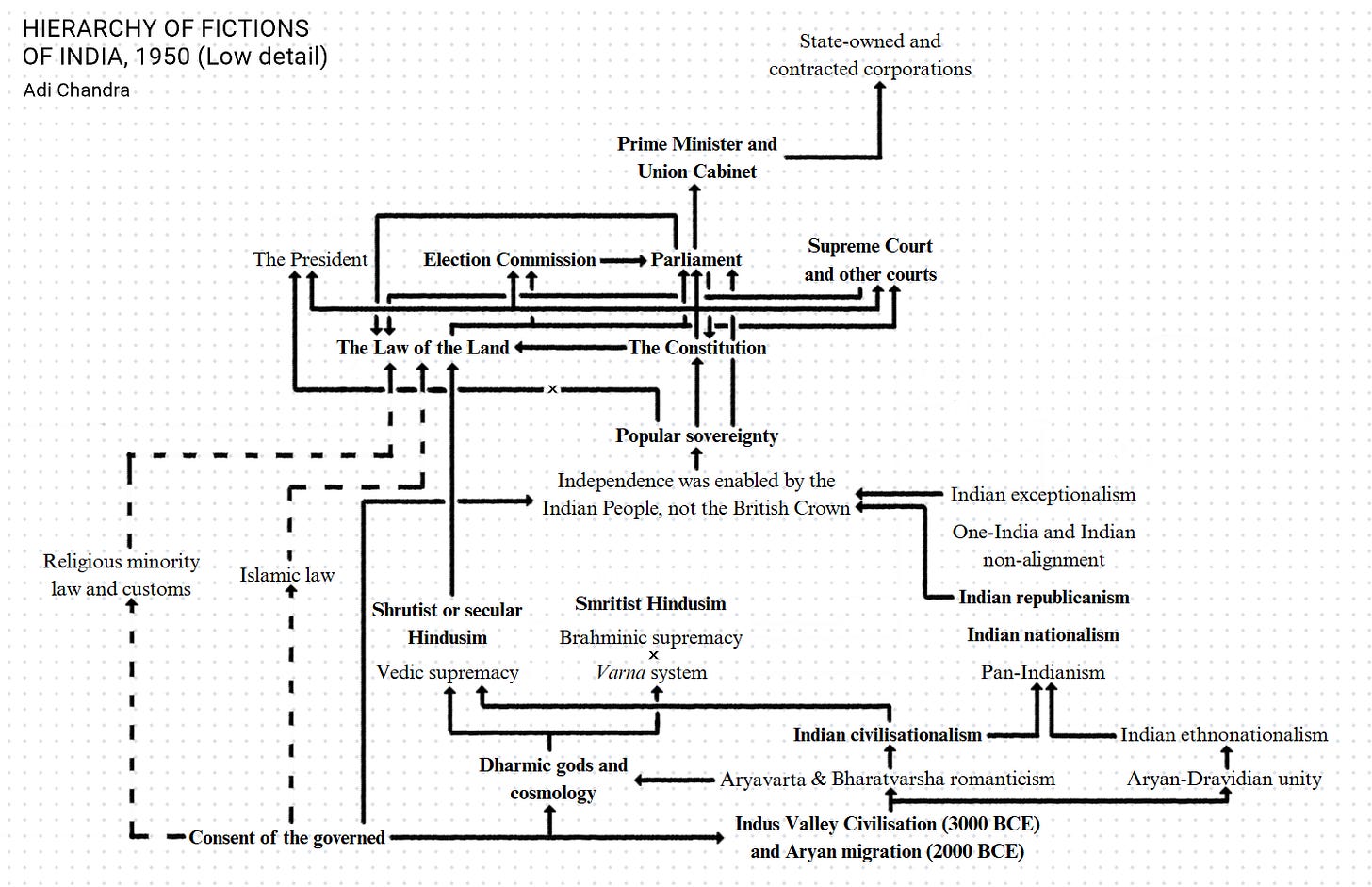

Put very simply, the first many fictions described above are the upper fictions of this part of the hierarchy in Country X, while the last few fictions, which are notably increasingly ontological, are the lower fictions. These fictions are not all strictly lies per se, and can be legal, historical, mythological, metaphysical, ethical, scientific, pseudoscientific, or of any other type. Despite how I have illustrated the concept above, a hierarchy of fictions of a social group is not linear in structure, but is rather a complex and variable web in which most fictions each connect to multiple other fictions. Given below, for instance, is my attempt at drawing the present-day hierarchy of fictions that makes up the Indian state:

Examples of enduring hierarchies

Let us examine some countries which have mostly preserved the fundamental structure of their hierarchies of fictions for a very long time.

United Kingdom

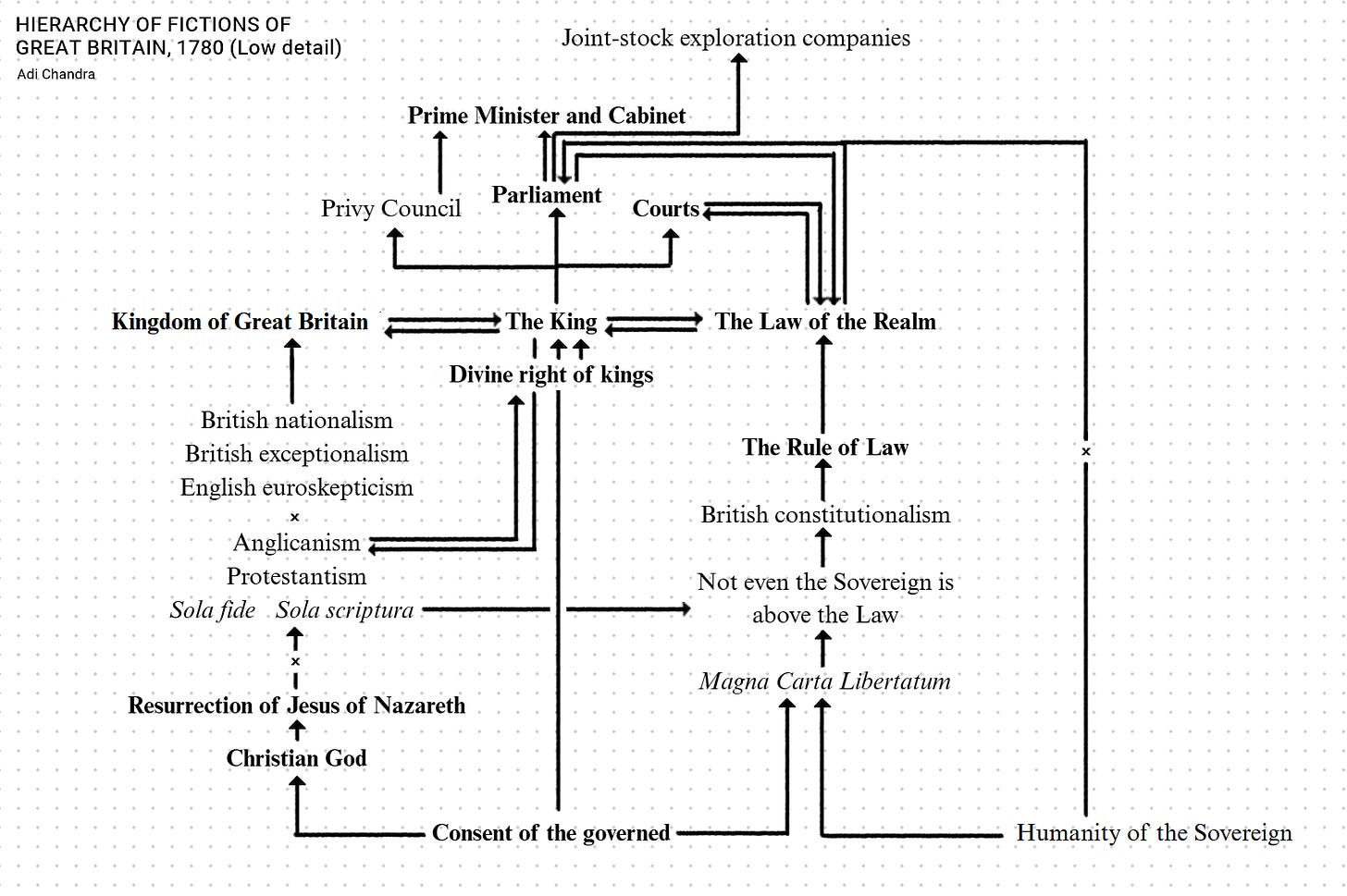

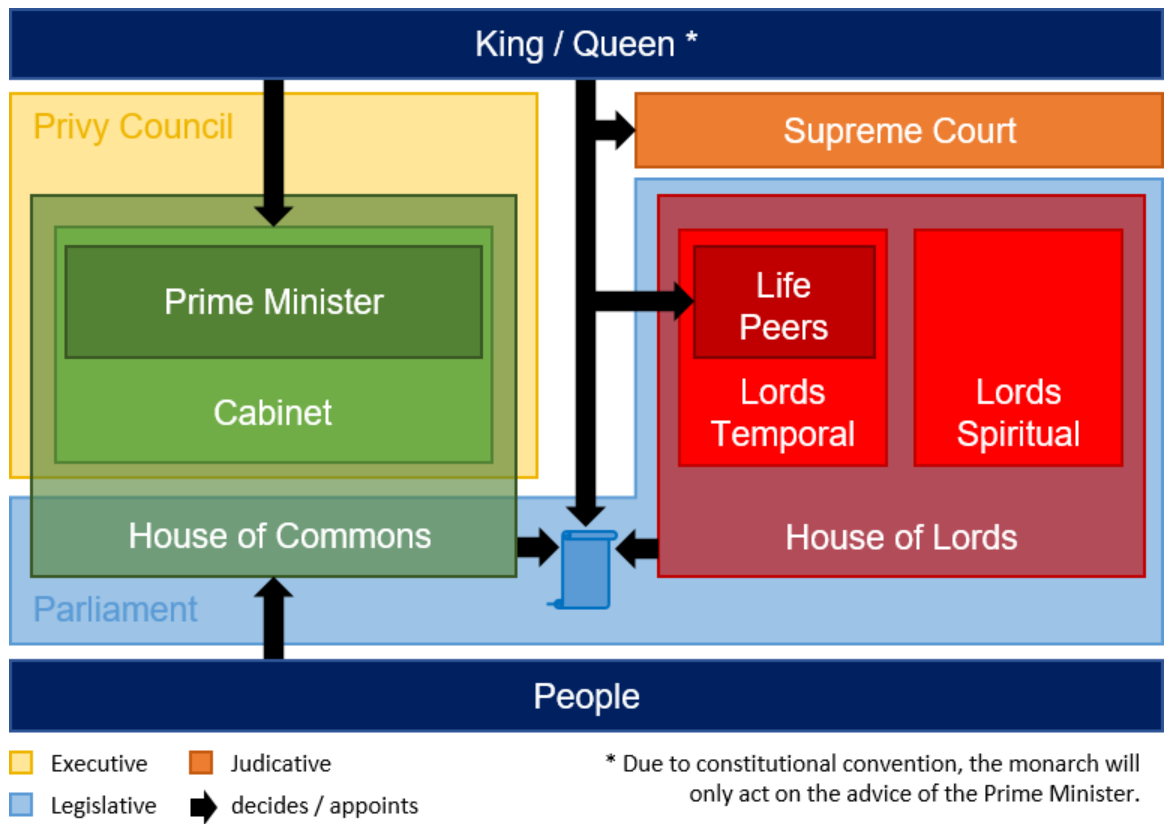

The United Kingdom is a fiction based in northwestern Europe. The reason why I admire the United Kingdom so much is because their fundamental constitution has remained unchanged for over one thousand years. The King (or Queen) who is the head of the modern British state occupies the same constitutional office as the King who ruled the English in the year 927 CE. It is not decreed anywhere in the higher levels of the law that the government is to be made up of responsible legislators elected by adult British citizens every few years. Rather, it was solely by convention and legislation that developed slowly over hundreds of years that Britain began to operate as a parliamentary democracy. The King almost always had an advisory council, but officers of government did not always sit as Members of Parliament. Witans, courts, and parliaments had almost always assembled, but such assemblies were not always responsible to the citizenry and did not always have the power to influence anything beyond taxation policy. These parliaments grew in power over the centuries and began to progressively limit the power of the English monarch, even beheading a king in 1649 to establish their supremacy. However, unlike the Humanity Declaration by the Emperor of Japan in 1946, the British Crown has never formally renounced one of its most important lower fictions—the divine right of kings—even though this has been defunct in practice since the seventeenth century. The King of the United Kingdom still nominally derives his legitimacy and authority directly from God, and his power to exercise his prerogative has been limited by the law that is still nominally his own. Therefore, while everything around the King has evolved and been reshuffled to allow the UK to make its place in the modern free world, its most critical lower fiction, that is, the British monarchy, has endured, and continues to lend immense institutional strength to the present-day democratic apparatus that is subordinate to it.

Charles Dance is one of my favourite actors. A friend recently shared a clip from the historical drama TV series The Crown, in which Dance plays Lord Mountbatten. In the clip, which is set in the middle of an alleged conspiracy to overthrow the government in 1968, Mountbatten discusses with his associates what an actual coup against the British regime would look like:

What all successful insurgencies have in common are five key elements—control of the media, control of the economy, and the capture of administrative targets, for which you need the fourth element, the loyalty of the military. Now, in Ghana and Gabon, this can be achieved with a handful of battalions, but here in the United Kingdom…

We would need to secure Parliament, Whitehall, the Ministry of Defence, and the Cabinet Office. The prime minister will be arrested, of course, along with other politicians still loyal. We would have to shut down the airports, air traffic control. Same with the train stations. Curfews will be put in place, martial law declared. And I haven’t even mentioned the police. It would take tens of thousands of unquestioningly loyal servicemen, and even in my heyday, I could never command that.

Which brings me to the fifth element. Legitimacy. Now, our government draws its strength from long-established institutions that support it. The courts, the body of common law, the constitution. For any action against the state to succeed, you’d have to overthrow these as well. But in a highly evolved democracy such as ours, their authority is sacrosanct. Which is why, gentlemen, a coup d’état in the United Kingdom doesn’t stand a chance.

Now that we have begun to appreciate the practical importance of a country’s hierarchy of fictions, I want to bring your attention to the fascinating research that won the 2024 Nobel Prize in Economics. Dr Daron Acemoglu, Dr James Alan Robinson, and Dr Simon Johnson showed that the economic success of a country is not just correlated with its institutional strength, but is caused by it (Acemoglu & Robinson 2012 and others). This means that a large, strong, interconnected, and stable hierarchy of healthy fictions is a climacteric factor in the making of a wealthy and powerful country. In the case of the UK, as hinted at by Dance’s excellent monologue, its strong and highly entrenched network of both lower fictions—like the monarchy, the divine right of kings, and the constitution—and upper fictions—like the democratic institutions and the state machinery that supports them—is cardinal to the country’s prosperity and security. Incidentally, this is why, in my opinion, British republicans who seek to abolish the monarchy exclusively because they think that it is an undemocratic or unnecessarily expensive institution are probably failing to realise that actually doing so might significantly weaken and destabilise the British state. Precedents like the French Revolution do not paint a pretty picture, given the hundreds of thousands of French lives and the trillions of dollars it cost to abolish the ancien régime.

On the surface, the UK and South Korea are both modern, developed, liberal democracies. However, it would be orders of magnitude easier to go to South Korea with “a handful of battalions” and replace the existing presidential republic with, say, a Confucianist constitutional monarchy, arguing that, for example, the modern South Korean state must establish itself as a continuation of Great Joseon to better legitimise its claim over the entire Korean peninsula, than to attempt something similar in the United Kingdom.

United States

The United States is a fiction primarily based in central North America. The country is particularly interesting because, despite being a much younger fiction in comparison to the ancient European monarchies, and even having had to evolve from a preceding fiction that was the Thirteen Colonies, its hierarchy of fictions is notably sizeable, strong, and sophisticated. I strongly—albeit controversially (Hammons 1999)—believe that the credit for this goes to the Constitution of the United States, which, at around 4,400 words excluding amendments, is one of the shortest written national constitutions in the world. Deriving its own legitimacy from such other key lower fictions as the Laws of Nature, the consent of the governed, and the liberalist axioms (“We hold these truths to be self-evident…”), the US Constitution focuses on establishing a strong foundational framework for the American republic, relying on broad, flexible language that allows adaptability over time through interpretation and amendments, rather than addressing specific issues, laws, and policies. The short length of this great instrument is what necessitated and incited the development of the enormous body of interconnected upper fictions on top of it, including but not limited to the tens of thousands of Acts of Congress, the tens of thousands of executive orders, the tens of millions of federal court rulings, and the uncountable conventions, regulations, declarations, statements, opinions, guides, directives, registers, and international treaties, which has made the United States one of the world’s most, if not the most, institutionally strong, mature, and sophisticated nations.

A country’s constitutional law is supposed to be one of its most important lower fictions. I think, in the specific case of a written national constitution, that the longer and more exhaustive it is, the weaker it is, because in trying to accomplish everything on its own, it both reduces the need for a large web of upper fictions on top of it and necessitates its own high malleability. The Constitution of India, which is the longest written national constitution in the world at around 145,000 words at the time of its adoption, has been amended 106 times since 1950 (as of writing this), while the US Constitution has been amended 27 times since 1789 (as of writing this), of which 10 amendments were made and adopted simultaneously in 1791 as the Bill of Rights. The Constitution of India endeavoured to be as complete of a body of law as it could be on its own, detailing even the most mutable aspects of the republic, such as the names and jurisdictions of the states of India (the map of the states of India today looks nothing like what it was in 1950). This need for constant tweaks, changes, and expansions that its very comprehensiveness obliges, causes an erosion of trust in the constitution and in the language therein. If a written national constitution is weak in this way, it makes it dangerously easy to reject said constitution, because one could argue that if an ostensible lower fiction does not properly support a large network of upper fictions and, in fact, needs to be constantly altered itself just to preserve the existing hierarchy of fictions, then it is not a good lower fiction at all and must be urgently abolished. (I am not saying that the Constitution of India specifically is weak as a lower fiction, but I am opining that is weaker than it could have been and than its American counterpart.)

Lower fictions that are insufficiently robust and durable can become a death sentence for their society. France burned through four republican and two imperial political systems precisely because of such constitutional weakness, which also claimed the deaths of such states as the Central African Empire, the Weimar Republic, Rhodesia-Nyasaland, the Kingdom of Libya, South Vietnam, the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan, and perhaps even the Soviet Union. On the other hand, as the Quran is to Muslims, the US Constitution has become a near-immutable object of worship for the American people, who are extremely confident in looking to it for guidance, for evolutionary interpretation, and for guaranteeing the Rule of Law in the United States. It is not a perfect document, with elements like the Electoral College, the appointment process for Supreme Court Justices, and the Second Amendment constantly becoming subjects of criticism. However, in the end, I believe that the US Constitution remains one of the most enduring and influential constituting instruments in history not in spite of its brevity, but because of it. American law is mind-numbingly complex and expansive, and that, as long as the Rule of Law itself as a fiction remains set in stone, is an incredible thing for the United States.

Other examples

Other examples of countries which have similarly preserved their hierarchies of fictions for very long include Denmark, Sweden, and Norway.

Key observations

The economic soundness, political stability, and sovereign position of a country are correlated with its institutional strength, that is, the size, interconnectedness, and health of its network of upper fictions.

The strength or health of a fiction or network of fictions refers to their relative respectability, stability, predictability, and immutability within a society.

If a lower fiction is unable to sustainably support a large, dense, and healthy network of upper fictions, and/or is overly plastic itself, it is weak and prone to collapse.

A stable hierarchy of fictions has, firstly, legitimacy, meaning the connections between the fictions are strong, durable, and grounded in robust lower fictions that can support the structure in-perpetuity. The hierarchies of fictions observed in today’s enduring hierarchies are both highly vigorous and secured by such inviolable and venerated institutions as the monarchy of the UK and the Constitution of the US.

A stable hierarchy of fictions has, secondly, longevity, meaning it has demonstrated the ability to withstand the test of time. Importantly, this includes adaptability, meaning the hierarchy is able to slowly evolve with the changing times. Some of the enduring hierarchies that exist in the world today have survived for over a thousand years and counting, creating a high degree of trust in their institutions and thereby giving these countries an advantage in power and wealth on the global stage.

Hierarchies of fictions that are adaptable enough to evolve organically with time (like the common law systems of both the UK and the US) enable long-term stability and persistence as the decades pass and the world changes.

Examples of altered hierarchies

Let us now look at some countries that have substantially changed or even completely replaced (once or many times) their hierarchies of fictions relative to those of their preceding polities.

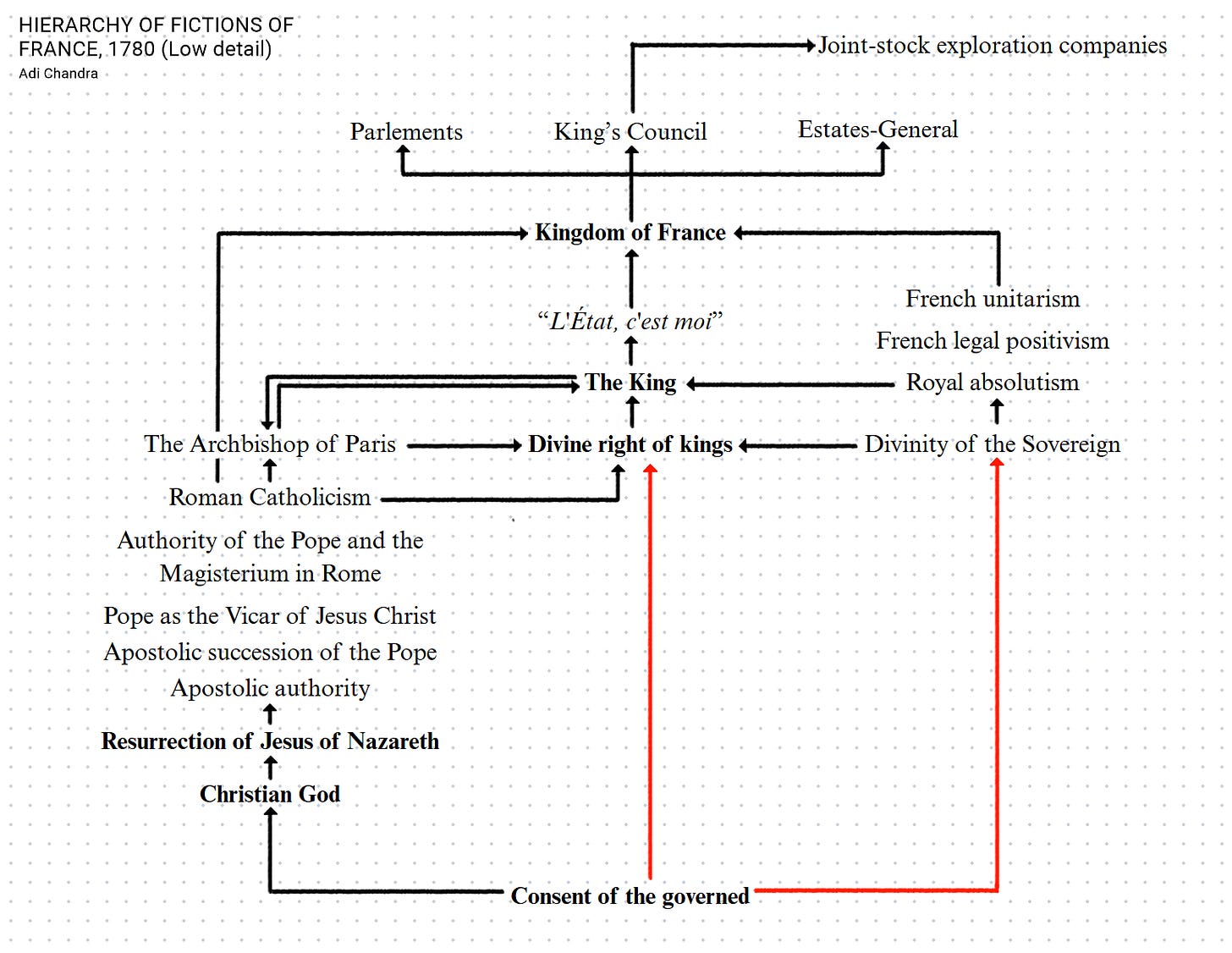

France

France is a fiction based primarily in western Europe. Following the fall of the Kingdom after a thousand years of existence, four republics and two empires perished to ultimately make way for the current Fifth Republic, which has been the French state since its establishment by Charles de Gaulle in 1958. Looking at French history, I became interested in what exactly was it that caused ideas critical of a thousand-year-old political system to flourish with such extremely broad popular backing. The ancien régime supposedly had both legitimacy (divine right of kings) and longevity (an essentially unbroken constitution since 843 CE), and yet, it was met with violent destruction and was replaced with a form of government that was considered so dangerously fairy-tale-sy that it angered essentially all of the rest of Europe and incited nine destructive wars. Why?

After Rome had fallen, Europe was effectively a subsistence agrarian economy with declining cities, collapsed trade, and extreme wealth inequality. The estimated GDP per capita in western Europe in the ninth century was around $600-800 (in modern USD), which is well below the World Bank’s extreme poverty line of around $900. Even though Europe at that time was indeed not a modern cash-based market economy, this is still a brutally low level of wealth— no surplus resources, no private property, and famines, disease, and feudal injustices wiped out scores of commoners every year. Most of the wealth was in land that was owned by the lords and the churches, and the serfs had essentially no financial assets. In the fourteenth century, the Black Death had come and gone, massively reducing the labour supply and thereby skyrocketing wages for the commoners. Serfdom had died in many areas, the survivors of the pandemic had inherited land and wealth from the dead, agricultural technology had improved, the manorial economy had stabilised, and a middle-class of merchants and artisans was emerging in such trade cities as Venice, London, Bruges, Florence, and, indeed, Paris. The GDP per capita then must be around $1,000-1,500, meaning more food and stability and less suffering and death. Five hundred more years went by, and the Age of Enlightenment, the Scientific Revolution, the cottage industry, early capitalism, banking, finance, joint-stock corporations, and colonial wealth inflows then led western European commoners into the nineteenth century, by which time the estimated GDP per capita was $2,000-$4,000. Although very slowly and very unsteadily, the individual wealth of western European commoners had increased fivefold from the ninth to the nineteenth century, thanks to the increase in productivity per capita caused by gradual technological, sociocultural, and philosophical progress (Maddison et al 2020).

Let us rewind once again now so as to explore how pure fortuity bred very different hierarchies of fictions in England and France. We have, on one hand, the Plantagenet English king John (r.1199-1216), who happened to be an incompetent failure and on top of that an unjust autocrat, losing the Angevin Empire and terrorising the English nobility with high taxes, arbitrary punishment, and constant and expensive military defeats. On the other hand, we have the Capet French king Philippe II (r.1180-1223), who happened to be a military genius, a master of statecraft, and a man who married shrewd pragmatism with relentless ambition, turning European politics upside-down by defeating the Plantagenets, transforming his fragmented feudal state into a powerful and centralised kingdom, and, most importantly, significantly expanding and entrenching royal authority in France. Philippe II happened to defeat John in the Battle of Bouvines in 1214, taking over most of England’s continental holdings. This made the authority of the French sovereign unchallenged in western Europe, while John faced a revolt by his frustrated barons and was forced into agreeing to the Magna Carta in 1215, first birthing in England the concept of the Rule of Law and beginning to slowly erode the system of absolute monarchy. Of course, there were revolts by feudal lords in France too, but unlike in England, such uprisings were militarily crushed by the increasingly powerful French king, such as in the Albigensian Crusade of 1209-29. Therefore, while England’s humiliating defeat in the 1213-14 Anglo-French War caused it to begin to gradually acknowledge that not even their king is above the law and move toward a common law system of judicial precedents, parliamentary government, and, eventually, limited democracy, France’s victory in the same war caused it to move toward royal absolutism, culminating later, of course, in the Bourbon dynasty.

Let us bring ourselves now to the year 1780 and look more closely at these two states. Great Britain was ruled by the British Parliament, of which the House of Commons comprised of legislators elected by landowning men all over the country. Parliament made laws, determined taxation, and selected the ministers of the executive government through their confidence or lack thereof. The King was still influential, but was bound absolutely by the British constitution, with no power to directly legislate, execute, or adjudicate. In France, on the other hand, at this same time, the King ruled by decree. Parlements could, on paper, challenge royal legislation, but the King could override any such challenges with the lit de justice, and even punish anyone without trial through lettres de cachet. The government was extremely centralised, with intendants enforcing the King’s will across France and no elections or popular representation at any level to speak of.

We have studied in detail how and why the hierarchies of fictions in the two countries differed in this way at this time, and before that, we looked at the rising gross product in western Europe from the ninth century to the nineteenth. In 1780, France had a respectably large economy on paper, but in reality, most of its wealth was controlled by the tax-exempt clergy and nobility, while the Third Estate, comprising of serfs, urban workers, and even skilled professionals and rich merchants, held little assets and bore all of the tax burden, including royal taxes, feudal dues, tithes, and even mandatory unpaid labour. The government was deeply in debt because of expensive wars and extreme fiscal mismanagement, but instead of taxing the wealthy First and Second Estates or providing relief to the public during times of bad harvests and mass hunger, King Louis XVI was forced by his nobles and magistrates into taxing the Third Estate even more. Now, the GDP per capita of France in 1780 was around $1,800 (2020s USD PPP), up substantially from the estimated $1,300 in 1220 (Maddison 2007). In Paris—the heart of France—approximately 90% of the men of the Third Estate were literate, 30-40% were deeply politically aware, and 10-15% (bourgeoisie and professionals) were even wealthy (Houston 2011, Garrioch 2015). As a people become wealthier and more educated, it becomes increasingly difficult to oppress or mislead them, and yet this is precisely what the French royal government was doing in the eighteenth century. Crushing taxes, arbitrary arrests, grain price manipulation, the winter famines of 1788-89, the quarrel between the finance ministers and the parlements, high censorship, violent crackdowns on protests, the nobles’ scornful mockery of the poor’s suffering, and “qu'ils mangent de la brioche”. The nail in the coffin came when Louis was forced to call the Estates-General in 1789, and the outrageous disenfranchisement of the commoners, engineered by the top two estates through the parlements, was shamelessly put on full display, after which the Third Estate unilaterally declared itself the National Assembly and subsequently launched the French Revolution.

Violent revolutions do not fix economic crises. They do, in fact, the opposite. The French Revolution, specifically, cost the country $1-2 trillion in modern US dollars and killed well over 500,000 people. The GDP of France shrunk by 25-30% between 1789 and 1795 and the purchasing power of the French people declined by up to 99% (Franck & Michalopoulos 2017). However, the Revolution in 1789 came nonetheless, and this was because the foundation of France’s hierarchy of fictions had completely collapsed, giving way then for the French people to take over and establish whatever alternative hierarchy they desired. As for why such a collapse occurred, this provides massive insight for the furtherance of Vindanist theory, because it seems that the cause of the fall of the ancien régime was the withdrawal of the consent of the governed. Indeed, we observe that the consent of the governed is the lowest of the lower fictions that hold up the hierarchy of fictions in any society, implicitly or explicitly. This means that the strength of a fiction or web of fictions does not depend only on how robustly it is legitimised by other fictions or how well it has endured over time, but also on if the general population consents to and believes in the existence of said fictions. Therefore, all human institutions—governments, laws, religions, economies—are ultimately upheld by their active or passive acceptance by the society that they are in. No matter how much a regime claims that its power derives from gods, tradition, law, superiority, or conquest, its actual, practical survival depends on enough people accepting its legitimacy, whether through belief, habit, or fear. If the people en masse withdraw this consent, the entire institutional structure of the society collapses. Remember that if people do not believe, money is but paper, borders are but imaginary lines, and countries are but rocks and rivers. At the height of the ancien régime, the people did believe—in sacral kingship, God’s mandation, and the sovereign’s unbounded power. After all, Louis XIV—the Sun King—who reigned during the peak of the Age of Absolutism and was a fierce adherent to the divine right doctrine, made certain that, absent a superior spiritual power, the French king’s authority was utterly unquestioned. However, Louis XVI was not Louis XIV. We are beginning to observe that a salient property of all fictions is that they are, from time to time, challenged. Therefore, fictions—especially lower fictions—must be able to withstand attacks, that is, challenges to their legitimacy, for the hierarchy of fictions in their society to survive.

If, for comparison’s sake, we return to the hypothesis of Country X that we discussed earlier in this paper, we will find that Country X’s base fiction, the ‘God of Nature,’ will generally withstand all high-level attacks on its legitimacy because a diety is, by definition, supernatural and therefore can neither be empirically verified nor disproved. The King of Country X claims that he is descended from this God of Nature, which also cannot be disproved because the royal line is so long that it blurs on the past end and because, again, the god in question is outside of the observable bounds that we exist in. So far, this is similar to the fiction of the Christian God and to how the monarch claimed His mandate in 1780s France. However, in Country X, instead of governing himself, the King has instead chosen, since the aforementioned Democracy Edict, to legitimise other fictions, that is, the Constitution and the democratic government, which are obviously exceedingly easy to consent to (consensus democracy), that govern in his name. This democratic government, which the King legitimises and voluntarily delegated all political power to, forms a free welfare state that takes care of its people and enables them to build, innovate, and thrive. The people of Country X will, therefore, not withdraw their consent to the existence of the King because the strength of the fiction that is the monarchy of Country X exceeds the aggregate instability and mutability of Country X’s upper fictions, being anchored in a set of ancient lower fictions that are both unverifiable and irrefutable and, through the King, furnishing an enormous amount of institutional vigour to the democratic government that is so loved by its people. Similarly, the people of, say, Denmark do not withdraw their consent to the existence of their own monarchy because the strength of this fiction—legitimised by over 1,300 years of its endurance, by ancient law, by conquest, and by God—currently exceeds how unlivable the country is made by its upper fictions, that is, its parliament, government, civil service, police, private companies, economy, justice code, et cetera (Denmark is a developed country that ranks among the best in the world to live in).

We are in a position now to observe why exactly the monarchy of France, unlike that of Country X, the UK, or Denmark, collapsed in 1789 due to the withdrawal of the consent of the governed:

The people of France in the 1780s believe that the King of France, by the mandate of God, is the absolute, quasi-divine, unquestioned authority of the realm, from whom all state power flows. At this time in France, the people are much more literate (around 50% of men and 30% of women) than they were during the time of Louis XIV (around 25% of men and 12% of women in 1650) (Melton 2001), and also the wealthiest (as discussed before) and most politically aware that they have ever been during the ancien régime. They know well of British constitutionalism, the recent American Revolution, and the domestic disasters and grievances that the newspapers detail.

France in the late 1780s is caught up in a massive economic crisis due to crippling debt and high financial mismanagement.

King Louis XVI is advised by his finance ministers, most notably Turgot, Necker, and Calonne, to pass laws to tax the First and Second Estates in order to raise enough revenue to alleviate the crisis, given that the Third Estate has already been extremely overburdened for a long time.

Said laws are blocked by the Parlement of Paris, which sides with the ultra-wealthy and refuses to register the royal government’s fiscal reforms, misleading the populace by posing as the “defender of the ancient liberties of the men of France”.

In response, Louis attempts to enforce his reforms by decree through the lit de justice in the Parlement of Paris on at least three separate occasions, but the court disregards these sessions and upholds its refusal of the laws.

Louis then exiles all the magistrates of the Parlement of Paris to the city of Troyes, permanently barring six of them from sitting in the court and even arresting two senior jurists. Still, the court refuses to register the laws.

Louis then deprives of all authority and dissolves the Parlement of Paris, replacing it with a plenary court.

The nobles and the commoners, fearing royal tyranny by the unpopular and financially incompetent king, are outraged, and massive protests and riots break out in several cities. In the southeastern city of Grenoble, for example, people throw heavy roof tiles down at royal soldiers to defend the local parlement, on what later comes to be known as the ‘Day of the Tiles’.

In the face of the widespread rebellion, Louis is forced to reinstate the Parlement of Paris within only three months of dissolving it, even before his plenary court could register his tax reforms.

The Parlement of Paris continues to uphold its rejection of the King’s tax laws, ruling that such a change can be enacted only after it has been approved by the Estates-General, which has not assembled in 174 years.

Louis concedes defeat and is forced to convoke the Estates-General.

This conflict between the King and the parlements incites a fatal constitutional crisis in France. (Baecque 1994)

The people observe, in this way, that the authority of the King of France is not absolute in reality, that the word of the King is not always law, and that his own courts can successfully question and reject the King’s direction.

Through this observation at (13), the people now understand that the sovereign is not divine and untouchable (as Philippe II or Louis XIV were thought to be), but human and limited. Therefore, the consent of the governed to the fiction that is the divinity of the French sovereign is revoked.

Through the observation at (13) as well as through the emerging Enlightenment ideas of this time, the people now also understand that the Christian God has not, in fact, mandated the King to reign over France because said King’s will was blocked by earthly institutions (the parlements, the nobility, the Estates-General, etc), which should have been impossible for an invincible ruler truly ordained by the Almighty. In previous centuries, strong, commanding kings (like Louis XIV) had justified their alleged divine right by simply dominating all opposition, but Louis XVI was plagued by repeated political failures, forced concessions, and very high unpopularity. Therefore, the consent of the governed to the fiction that is the divine right of kings in France is revoked.

As this understructure is removed on the eve of the French Revolution, the hierarchy of fictions of France tips to one side and the King as an absolute monarch loses the vast majority of his legitimacy, directly causing the state and its institutions—the government, the courts, and the estate system—to lose most of their legitimacy as well.

The strength of the lower fiction that is the absolute monarchy of France now no longer exceeds the combined instability and contestability of the kingdom’s upper fictions, which only delivered misery, inequality, injustice, and death.

France’s hierarchy of fictions collapses.

So, in the thirteenth century, the French king Philippe II’s decisive victory at Bouvines eventually created a France where all law came, unchallenged, from one man, while the English king John’s humiliating defeat, loss of authority, and political concessions gradually moved England toward constitutionalism, parliamentarism, and democracy. Ironically, however, this also came to be exactly what allowed Britain to survive into the modern age, while France’s absolute monarchy proved fatally weak and inflexible in the face of rising individual wealth, literacy, and political awareness in the middle of a severe economic downturn, causing the citizenry to violently reject the existing hierarchy of fictions and, subsequently, Versailles to fall.

India

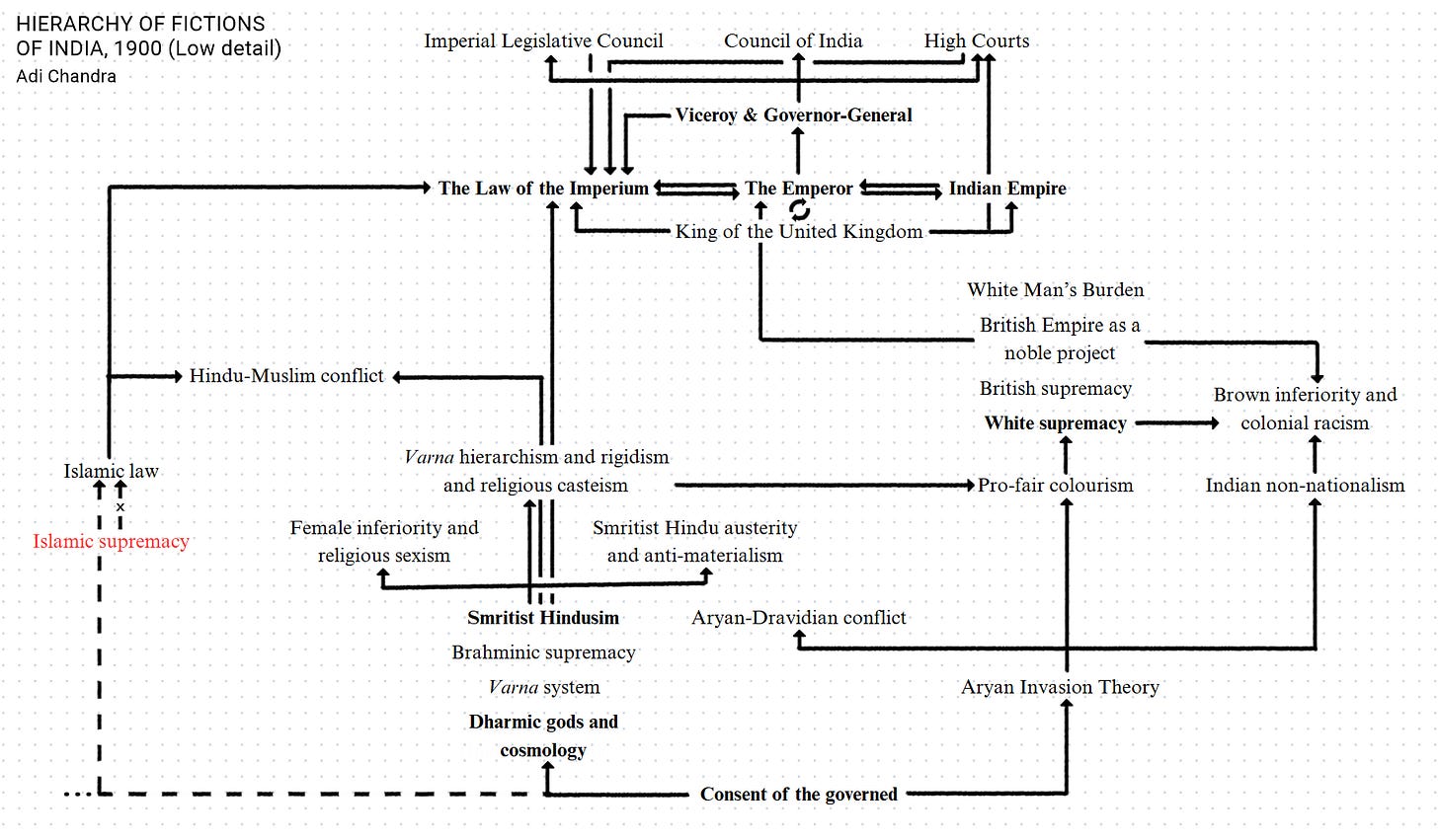

India is a fiction based in South Asia. Its ancient, five-thousand-year-old hierarchy of fictions underwent centuries of corruption from the sociocultural devolution engineered by the Brahminic clergy during the Middle Kingdoms as well as the invasion of Muhammad of Ghor and the subsequent defeat of Prithviraja III in 1192. Later, British corporate interests in South Asia instigated the rapid and complete dismantlement of Indian imperial and regional institutions after the fall of the Marathas in the mid-eighteenth century, and by 1858, the United Kingdom controlled half of the Indian subcontinent and dictated the foreign policy of the many kingdoms in most of the other half.

The reason why, in my opinion, a study of India’s hierarchy of fictions is important is because it was designed from scratch inside the heart of a destitute country after eight hundred odd years of the dormancy of its foundational dharmic civilisation. The Muslim invaders first replaced the Aryan and Dravidian nobility that were the earliest hierarchs of the land, following which the British drained, looted, deindustrialised, and comprehensively unmade the Indian Empire, reducing the country’s share of the global gross product from 25% in 1700 to 4% in 1950 (Clingingsmith & Williamson 2005). It was the Gandhi-led nationalist movement of the twentieth century that actuated the principle nationbuilding project that has created the modern Indian state. The British Parliament’s 1947 Indian Independence Act set up India and Pakistan as Australia- or Canada-style Commonwealth realms, with the King of the United Kingdom (and former Emperor of India) reigning in personal union as the King of India, the Governor-General of India as his local representative, and the elected Parliament as the actual political authority of the dominion. Unlike in France, the Indian “revolution” during the nationalist movement was neither violent nor rapid, and yet this hierarchy of fictions set up in India by London—which was supposed to last forever—only did for less than three years from 1947 to 1950, when the Republic was born.

As we well understand by now, societies are built on Vindan’s fictions—myths, histories, belief systems, and institutional structures that their peoples subscribe to and are united by. However, Vindanism is far from the invention of institutional anthropology or social constructionism, but rather just a (hopefully) new perspective on these highly active, decades-old fields of academia. The Western-exceptionalist British colonists in India built their empire on top of a complex pipeline of fictions, sometimes deliberately and calculatedly crafted and other times organically arising, meant to delegitimise Indian institutions, divide the Indian people, and justify the British Raj. Indeed, many of these fictions were in furtherance of the ‘White Man’s Burden’ philosophy, that is, fabrications, misinterpretations, and distortions intended to disarm and subjugate Indians and institutionalised through education, administration, and media. Listed below are some of the most central of these fictions:

“Four thousand years ago, fair-skinned Aryans invaded India and defeated and subjugated the dark-skinned Dravidians so as to establish Vedic civilisation” (Aryan Invasion Theory, AIT). This served to divide northern and southern Indians on the basis of this alleged ancient racial conflict and assert that all Indian civilisation had always been a foreign imposition. Thereby, this also became a justification of British rule in India, in which a white-skinned people came and dominated the darker-skinned locals and brought civilisation and order to the subcontinent, which was, at least according to the precedents supposed by the colonists, just how things were supposed to be.

“India is but a geographical expression and has never borne any unified societal identity, only ever consisting of fragmented and warring ethnicities and kingdoms.” This was designated to delegitimise the nationalist movement at its roots, arguing that a nation that had never existed cannot be fought for.

“India was a collage of backward and barbaric societies—self-sabotaged by an oppressive caste system, cruel practices like the sati, a pagan and incoherent religion, a severe lack of education, and arbitrary jurisprudence—until the British came and civilised the locals.” This narrative was rooted in the internal corruption of the priestly orthodoxy during the Middle Kingdoms, Smriti compositions like the Manusmriti and the dharmashastras, and the casteism, sexism, and dogmatism that the Brahmins in that period created. Once again, it was used to divide the Indians, entrench White supremacist beliefs, and justify British colonialism. Following from this and related fictions, the benevolent despotism idea also started to emerge in earnest as the British Empire was weakened after the World Wars.

“The ancient and medieval Indian empires and kingdoms were fragmented, weak, short-lived, superstitious, pagan, temple-obsessed, and casteism-ridden polities, and contributed disproportionately little to the world.” The British Raj systematically distorted Indian history to justify colonial rule, painting a deeply ideologically skewed and unempirical picture of the country. Their goal was to show that India had an undistinguished and unillustrious past, demonstrate that Indians were incapable of self-rule, and position the British Empire as a legitimate civilising force. They selectively exaggerated failures, erased successes, and warped popular beliefs.

We can imagine, therefore, that the hierarchy of fictions in India at the end of the nineteenth century looked something like this:

Gandhi returned to India in 1915.

The twentieth century was indeed a time when everything was rapidly coming together in all departments of the nationalist project. Such archaeologists and historians as Daya Ram Sahni, R.D. Banerji, James Prinsep, D.R. Bhandarkar, and K.P. Jayaswal made critical discoveries on the ancient Indus Valley Civilisation, uncovered and deciphered the edicts of the Magadhi Indian emperor Ashoka the Great, and returned Maurya, Shunga, and Gupta antiquities to national memory. Artists, thinkers, and spiritual insurgents like Rabindranath Tagore, Swami Vivekananda, and Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay rejected colonial epistemology and built on scholarly advancements to rebirth the idea of Indian civilisationalism, shifting critical connections in India’s institutional scaffolding. Military leaders and revolutionaries like Subhash Chandra Bose, Bhagat Singh, Chandrashekhar Azad, and Rash Behari Bose radicalised the national consciousness and afforded swingeing loudness and urgency to the countrywide rejection of the British-imposed hierarchy in India. Lastly, political leaders in the Congress and elsewhere carefully engineered the break of legal continuity that replaced the British-based monarchy as the central source of legitimacy in the country with the Indian people, which, in the end—confirming the broad success of the project—worked.

First, let us return to the previously discussed British-erected fictions that made the Raj, which were all later challenged and refuted by empirical scholarship and extra- and post-colonial research like so:

Modern scholarly consensus holds that the coming of the Aryans from the Central Asian steppes into India was in the form of gradual migration and integration rather than a large, singular, violent invasion, that the Aryans and Dravidians have lived together and intermixed for thousands of years, and that the Dravidians lived in advanced urban centres in the Indus Valley long before the establishment of Aryavarta (Witzel 2005, Sharma et al 2005, Sahoo et al 2006, Pathak et al 2018).

Most modern Indian ethnic groups descend from either the Ancestral North Indians (ANI, associated with Aryans) or the Ancestral South Indians (ASI, associated with Dravidians), and moreover, because of the long period of Aryan-Dravidian admixture thousands of years ago, nearly all modern Indian nationals have genetic contributions from both of these primary ancestral groups (Moorjani 2013). Additionally, Golden Age empires like Magadha, the Guptas, the Cholas, the Rashtrakutas, and the Kushanas—all linked by their adherence to Vedic culture and religion—spread across huge parts—sometimes almost all—of the Indian subcontinent and unified their peoples under common cultural, spiritual, and political frameworks that developed over time into a shared Indian identity and deep civilisational coherence that continues to thrive today (Sougaijam 2016, Gourav et al 2023, Kumar Pandey 2025).

Even though the Brahminic sociocultural reengineering of the Hindu civilisation during the Middle Kingdoms very likely did lead to a sharp decline in living standards, internal unity, productivity, innovation, and military strength in India (stay tuned for my upcoming paper on this subject, ‘Neo-Shrutism’), firstly, the aforementioned Smriti texts contradict and violate the constitutional Shruti scripture of Hinduism that birthed Vedic (and Indian) civilisation, secondly, most societal corruptions in India were not widespread or universal in Hindu society but rather had both regional presence and opposition (Eaton 1993, Jackson 2003, Yang 2008, The Missionary Herald 1829, Lord Bentinck 1829) and thirdly, most reforms to remove these problems came from within Hindu and Indian society (Mohan Roy, Phule, Vidyasagar, Saraswati, Ramabai, Besant, Ambedkar) (Dirks 2001) and not as colonial gifts, while the British furthered casteism, division, and discrimination (Bayly 2001).

Ancient and medieval Indian empires and kingdoms had flourishing development, sophisticated bureaucracies and legal systems, vast trade networks, enormous scientific investment, luminous art and architecture, and a pan-Indian vision. Mathematics was effectively invented in India with the development of the decimal system by Aryabhata and Brahmagupta (George 1998, Kaplan 1999), thereby enabling the modern world we live in today. Indians were also among those who pioneered calculus (Shukla 1984, Cooke 1997, O'Connor 2000), trigonometry (Boyer 1991), astronomy (Thompson 2007), classical physics (Bose 1988, Pickover 2008), surgery (Meulenbeld 1999), metallurgy (Feuerbach 2002), civil engineering, military technology, and linguistics (Bod 2013, Böhtlingk 1998). The Indian subcontinent made up around 32% of the global gross product during the height of Magadha in 250 BCE and around 29% during the Gupta Empire in 500 CE (Maddison 2007). The Indian Empire under the Mughals as well as the Marathas produced about 25% of the world’s industrial output until the end of the eighteenth century, with key industries being textiles, steel, shipbuilding, and foodstuffs (Clingingsmith & Williamson 2005, Shcmidt 2015).

Then, when Indian independence became imminent, the UK’s 1946 Cabinet Mission Plan envisaged the Constituent Assembly (elected through the provincial assemblies across India) and tasked it with drafting a constitution for the future independent dominion before submitting it to the British Parliament for approval. This would have perpetuated much of the foreign hierarchy of fictions that the British had championed in India (with the aforementioned Australia- or Canada-style political systems), likely leading to a continued erosion of Indian values, cultures, and legal traditions. The Constituent Assembly, led by B.R. Ambedkar, B.N. Rau, and Jawaharlal Nehru, pioneered, therefore, a new fiction to finally reclaim the civilisation-state that their people had long lost, which is now called constitutional autochthony. This is how it worked:

At independence in August 1947, all political legitimacy in India emanates from the King of India (George VI) at the base. Section 8 of the UK’s Indian Independence Act formally recognises the Constituent Assembly as both the now-independent India’s provisional national legislature as well as the framer of a constitution for the country. The Cabinet Mission Plan had ruled that the new constitution, once complete, must be greenlit by the Governor-General (Chakravarti Rajagopalachari) and ratified by the British Parliament before it comes into force in India.

The Constituent Assembly, which is legitimised by the British Parliament and its Indian Independence Act, assumes its powers and responsibilities in the Dominion of India starting 15 August, 1947 (after it split in the Partition).

The Constituent Assembly finishes drafting the Constitution of India by late 1949.

However, in blatant violation of the Indian Independence Act, the Constituent Assembly does not present the finished Constitution to the Governor-General.

Then, as another critical violation of the Indian Independence Act, the Constituent Assembly refuses to submit the finished Constitution to the British Parliament for review.

Moreover, when the Constitution comes into force in India, it repeals the Indian Independence Act, along with other British statutes enforceable in India, in its Article 395. This is not something that the Constituent Assembly was authorised by its legitimising fiction—the Indian Independence Act—to do.

(4), (5), and (6) have no support (are illegal) within the current hierarchy of fictions in India.

Therefore, under the current setup, the Constitution is illegal and illegitimate.

However, as the Constitution commences in India, it seeks instead to install itself into India’s hierarchy of fictions by means of another legitimising fiction—the Indian people. This would establish the principle of popular sovereignty, that is, national sovereignty lies with and all state powers flow from the Indian people, and not the British-based Crown.

Hoping this would work, the Constituent Assembly submits the Constitution to the Indian people for adoption on 26 January, 1950.

The consent of the governed is indeed granted to the fiction that is popular sovereignty and thereby to the fiction that is the Constitution. At the same time, the consent of the governed to the fiction that is the monarchy of India is revoked.

In this way, as the Constitution commences in India, the previous, British-imposed hierarchy of fictions is immediately and automatically replaced by the one superintended by the Indian leaders in the Constituent Assembly, and the latter, held up sufficiently well by the consent of the governed, stabilises easily.

The Indian state that was previously the Indian Empire and the Dominion of India is now the Republic of India.

By 1950, the hierarchy of fictions of India looked something like this:

Today as well, the Constitution remains firmly entrenched at the base of India’s political system, keeping strong the country’s principle of constitutional supremacy, unlike the parliamentary sovereignty that exists in the UK. Whereas in the UK, the British Parliament can do basically anything it wants—be it limiting freedom of speech, selectively banning protests, creating government backdoors in online apps, or murdering their own citizens in Northern Ireland during the Troubles—in India, the Constitution is supreme—because it came from the ad hoc Constituent Assembly, not Parliament—and judicial review exists to enforce the principle—whereby the courts interpret the Constitution and can strike down any parliamentary legislation that they deem unconstitutional. Moreover, in Bharati v Kerala (1973), the Supreme Court also ruled that Parliament cannot alter the “basic structure” of the Constitution through amendments, which developed into the Basic Structure Doctrine that has since been adopted by many other common law countries as well.

India’s bloodless constitutional revolution worked because it was spearheaded by the country’s pre-eminent Vindanists—legal experts and jurists—who understood how human institutions work. The careful design of the 1950 revolutionary breach of legal continuity by the framers was an immensely difficult and fragile task, made possible only by the fifty years of struggle by the freedom fighters and scholars who dedicated their lives to the idea of an independent and popularly sovereign India. I personally think that the Constitution of India and the hierarchy of fictions that it installed is far from perfect, and am very strongly opinionated on the subject of potential improvements and even alternatives, but do, of course, concede to the fact that the current system is indescribably better to live in than a home that would have looked and felt utterly foreign.

Other examples

Other examples of countries which have similarly transformed, changed, or replaced their hierarchies of fictions are China, Russia, Israel, Brazil, Germany, and Ireland.

Key observations

The lowest base of a hierarchy of fictions houses:

Consent of the governed

Empirical facts of history, geography, biology, etc (‘Humanity of the Sovereign’ in the UK, ‘Aryan migration’ in India, etc).

No hierarchy of fictions can stand without the consent of the governed to its critical lower fictions. This consent can come through genuine conviction, habit or comfort, fear, or any combination of these. Vindan’s fictions only work when people believe in them, or “money is but paper”.

Fictions naturally come under attack from time to time and must be strong enough to withstand such challenges to their legitimacy.

If the strength of any given lower fiction is lower than the aggregate instability and mutability of the upper fictions that it supports, then said lower fiction may cave and become void.

Countries with overly rigid and brittle institutions (Kingdom of France, but also the Soviet Union, the Ottoman Empire, etc) eventually collapse under political and economic stress.

When remodelling a hierarchy of fictions, a skilled Vindanist will make sure that all fictions within his hierarchy are sufficiently legitimised for the structure to stand forever (Indian constitutional framers), while others may simply draw up any hierarchy they desire with empty hopes that it will sustain, only for it to not (French revolutionaries and subsequent republican, imperial, and royal statesmen).

Fictions are power

We have observed through our long study of Vindan’s fictions that institutions—both formal and/or codified (laws, constitutions, bills of rights, corporations, regulations) and informal and/or uncodified (cultural norms, business ethics, legal conventions, mythologies, popular philosophies)—play a fundamental role in determining a country’s power and prosperity.

Durable, respected, well-functioning, and predictable upper fictions (strong contract enforcement, independent judiciary and central bank, strict labour laws, inviolable property rights, adherence to the Rule of Law, etc) strongly encourage trade, investment, and work, and discourage rent-seeking behaviour. On the other hand, weak upper fictions, arbitrary laws and enforcement, and corruption lead to low credit ratings, capital flight, and economic stagnation.

Because entrenched and immutable democratic systems with checks and balances usually have strong upper fictions, they foster predictability and stability, which is crucial in enabling long-term economic planning, an entrepreneurial culture, and high investor confidence (Rodrik et al 2004). On the other hand, an autocratic regime with arbitrary, on-a-whim laws and enforcement may experience short-term growth spurts at times but, more often than not, rot in the long-term. People don’t like to work or do business in places where the rules of the game keep changing, and investors will demand risk premiums.

Countries that have upper fictions that have both longevity (they are long-established) and adaptability (they are able to evolve gradually with the times) generally tend to be excellent places to invest, trade, and work in because of very predictable policies and a stable framework to work within. In fact, there is evidence to suggest that common law systems may be superior in terms of enabling stronger financial markets and investor protections than civil law systems (La Porta et al 1998).

Countries with fictions that enable and reinforce a culture of respect, celebration, and pride for their ethnicities, cultures, and histories will produce proud and competitive people who will be more likely to work hard toward their collective prosperity. Similarly, fictions that create room for an inferiority complex may contribute to stagnation and brain drain.

Countries with strong legal frameworks and traditions often influence international law (US, UK, etc). Conversely, countries with weaker legal traditions rely on others' systems, subtly reducing their sovereign decision-making power.

et cetera

I strongly recommend this paper from the Committee for the Nobel Prize in Economics from when Acemoglu, Robinson, and Johnson won the award in 2024.

Vindanists at work

A Vindanist is a scientist who engages with Vindanism to study human fictions and bring about change in the real world. Let us explore how.

We go back one hundred years in Country X. The King, an admirer of Western constitutionalism and liberalism, orders a draft of the Democracy Edict from his most trusted Minister—a skilled Vindanist. The Minister gets to work.

Through study, countrywide surveys, and scholarly reference, the Minister conducts an audit of Vindan’s fictions in Country X, that is, maps out the key institutions of Country X, including its legal framework, political structures, educational system, economic policies, media, and cultural practices (that is, its upper fictions), as well as the prevailing myths, historical narratives, empirical facts, and shared philosophies that undergird those institutions (that is, the lower fictions).

The Minister identifies where all these fictions go in the larger web and how they connect to each other, drawing an accurate diagram of Country X’s hierarchy of fictions in maximal detail.

The Minister then picks up green- and red-coloured markers (a simplification) and begins to differentiate the networks of fictions in the diagram that encourage unity, innovation, and investment in Country X from those that compromise its political stability, human capital, economic health, etc.

For example, the beloved monarchy and the myths of the God of Nature that unify the kingdom, the ancient constitutional scripture that forms the basis of Country X’s legal tradition, and Country X’s history of affording very high legal and military protection to large businesses (both domestic and foreign) are coded green.

Meanwhile, weak labour laws, ad hoc judicial decisions, the extremely decentralised and arbitrary law enforcement system, and the lackluster school curriculum with multiple languages across the country and in which children learn little about their history and culture are all very red.

The Minister redraws the hierarchy of fictions so as to remove the red-coded areas and strengthen the green-coded ones, while making sure, through calculated and intricate manipulation via adding, removing, and editing other fictions, that this does not cause any part of the institutional makeup to lose legitimacy and topple. This new diagram will be the blueprint for Country X’s upcoming Constitution.

The Minister strengthens the central legitimising myth of Country X by adding “Scion of the Mighty Children of the God of Nature” to the King’s official regnal style.

The Minister plans to have the educational curriculum of Country X completely overhauled, requiring children to learn in detail about where their brave, fierce, and adventurous ancestors came from, what they built, discovered, and invented, how they developed their beloved language and culture, and why their modern descendants matter so much on the global stage today. The Minister will also require all schools to teach only in X-ish, the most commonly spoken language and lingua franca of Country X.

He will also include some study of Country X’s national religion—X-ism—and X-ism’s central scripture—the Laws of Nature—into the school syllabus, careful in clarifying what is real and what is just belief, and to not let this education come into conflict with the secularism or the freedom of faith that will soon be enshrined in the upcoming Constitution. Students will, however, learn in detail about how the Children interpreted the Laws of Nature, how they built their Temple in the capital of Country X ten thousand years ago, and how the King is directly descended from them and is therefore the most holy, the most wise, and the only legitimate lawgiving authority.

The Minister deletes from the diagram the red-coded fictions—arbitrary laws, unpredictable fiscal policy, irregular and archaic administrative regulations, outdated cultural beliefs that breed an inferiority complex among the populace, etc—which he plans to weed out through such state mechanisms as education, media, and law.

The Minister makes certain that the new upper fictions of Country X are durable, respected, and, above all, adaptable. Previously, Country X was a hotchpotch of religious-derived laws that were at places common-ish and at others civil-ish. In the new hierarchy that the Minister has designed, Country X’s brand-new highly adaptable yet vigorous case law system is entrenched, and, at the same time, strongly legitimised by the reinterpreted (discussed later) Laws of Nature.

et cetera

With the redesigned hierarchy of fictions planned out, the Minister drafts the Democracy Edict and installs it into the hierarchy of fictions of Country X like so:

The King of Country X is the sovereign lawgiver of the kingdom.

The King issues a royal decree called the Democracy Edict (authored by the Minister) which:

Orders a countrywide, constituency-based free and fair election of a group of one hundred representatives through universal adult suffrage. (This election, enjoined by the Minister, strengthens the consent of the governed to his new hierarchy. Smart!)

Invites said one hundred representatives to come together in the capital city and form a Constituent Assembly.

Requests said Constituent Assembly to draft a Constitution for Country X in line with the Minister’s new hierarchy.

The Constituent Assembly drafts the Constitution, complete with the following unalterable salient features:

It is as brief, rudimentary, and powerful as possible, never trying to do what statutes, court rulings, or administrative regulations are meant to. It also makes thoroughly clear on the very first page where it derives its legitimacy from:

By the power vested by His Holiness the King, Scion of the Mighty Children of the God of Nature, in the Most Loyal Representatives of the good X-ian People in this Constituent Assembly assembled, the X-ian People hereby ordain, establish, and give to themselves this Constitution.

It sets out a set of fundamental civic rights (including freedom of expression, freedom of religion, inviolable property rights, etc), establishes a robust, transparent legal system, guarantees unrestricted access to public information, protects independent contract enforcement, etc.

It establishes that Country X is subject to the Rule of Law, guaranteeing equality before the Law, due process, fair enforcement and trials, judicial review, etc.

It sets up a tripartite government with three separate and co-equal branches (the legislative, the executive, and the judicial branch), defines and demarcates their responsibilities and powers, and puts in place a comprehensive system of checks and balances.

It mandates free and fair elections regularly to elect representatives to national and local public offices through universal adult suffrage.

As the Constitution is being drafted, the Minister, with permission from the King, is also working on other key projects:

The Reinterpretation Edict reinterprets the thousands-of-years-old Laws of Nature to align with modern ideals of democracy and liberalism, focusing and expanding on the ideas that promote national unity, strength, learning, and development, and dismissing those that push divisiveness, austerity, discrimination, dogma, et cetera. State newspapers pick up the Edict as soon as it passes to educate the public on its contents with simple and accessible language. The songs, poems, plays, magazine entries, and books that come after also help a lot.

The Minister reaches out to Country X’s most popular magazines and top advertisers to design foolproof campaigns to inform the public about the “King’s Great Dream,” discussing how the strength of the collective X-ian people was lost from national memory for so very long (this war victory, that invention, this economic miracle, that cultural gem), how the Laws of Nature actually assert that Country X was always meant to be a liberal social democracy, how, ten thousand years ago, the Children of the God of Nature actually lived in what was basically a republic, and how the new Keynesian capitalist system is going to make everyone very comfortable and well-off.

The Great X Epic, composed in pure X-ish by the greatest living X-ian dramatist, is sanctioned by the Minister to tell the grand tale of the Children, the Temple, the Kings, and the rise of the noble and mighty X-ian people, and how it is the X-ians’ God-given destiny to create the perfect social democratic utopia and dominate the world through sheer economic might! The Epic also subtly but repeatedly attacks the old, “outdated,” “barbarian” version of X-ism while singing the praises of the new, post-Reinterpretation, reformed version of X-ism. Thanks to (secret) state support, the Epic becomes the bestselling book in the history of Country X, loved by the masses and by critics alike, and is adapted into equally sensational plays, songs, and films later.

et cetera

Word of mouth, debates, and education on all of the above are heavily encouraged, while the counter-culture is ridiculed and dismissed as unempirical and antinational. All anti-liberal, anti-capitalist, or anti-Rule of Law sects of orthodox X-ism are now considered lame, outdated, and scandalous, and the inferiority complex, historical illiteracy, and religious and traditionalist dogmatism that were prevalent among many X-ians before have now been destroyed utterly by the all-powerful state media and education machine.

The finished Constitution rides the largest wave of the nationalist milieu that the Minister has manufactured to come into force in Country X in a grand ceremony attended by the King and by millions of proud and excited X-ians.

The Minister has also created constitutional schedules, administrative laws, and day-zero statutes that are deployed alongside the Constitution:

The Minister rewrites labour laws from scratch to guarantee worker welfare, good working conditions, healthy working hours, parental leaves, etc.

The Minister creates a singular code of conduct for Country X’s law enforcement and codifies existing and new criminal laws into a uniform justice code enforceable countrywide.

The Minister centralises and standardises the educational system of Country X, mandating the use of X-ish as the sole medium of instruction, teaching students about Country X’s new political system, encouraging them to participate, debate, vote, and run for office, making them familiar with and proud of the history of the X-ian people and the mythology around X-ism, and training them to be world-class critical thinkers, innovators, creators, generalists, specialists, leaders, and team-players.

The Minister creates a code of operations for state media, directing them to educate the public on Country X’s new political system, encouraging them to participate, teaching them to innovate and create within the new liberal order, and keeping them updated on domestic affairs, all accessibly and transparently. The Minister ensures that non-state media in Country X remains fully independent.

The Minister codifies business regulations, expanding robust legal protection to businesses of all sizes and types, decreasing red tape, modernising the currency through decimalisation, etc.

The Minister strengthens due process by drafting a high-level code of conduct for all courts and tribunals in Country X to follow and mandating that no court operate or adjudicate in a manner that does not align with the Constitution.

The Minister makes certain that free healthcare, free education, affordable housing, good public transport, clean environments, etc remain universal rights in Country X.

et cetera

The Minister understands that the Constitution derives its legitimacy from the Democracy Edict, which derives its legitimacy from the King, who is still the sovereign lawgiver, meaning that the Constitution is not the supreme law of Country X yet per se. The King can still absolutely make any law he wants, order anyone to do anything, or deliver whatever justice wherever he wants even in this new hierarchy of fictions, completely overriding the democratic institutions newly established by the Constitution.

To resolve this, the Minister discusses the matter with the King and they establish a crucial constitutional convention—an unwritten but unbreakable rule—that no King of Country X will ever himself legislate, execute, or adjudicate again, even though he technically can. He will instead delegate all of his political powers to the democratic institutions that will govern in his name and by his authority. This enables the practical supremacy of the Constitution and makes the King a ceremonial figurehead within a constitutional monarchy, meaning that the word of the King is the supreme law of Country X de jure but the Constitution is the supreme law of Country X de facto. This also means that the Democracy Edict was the last royal decree in the history of Country X (unless, down the line, some future King wants to break this convention, issue another edict, cause a constitutional crisis, and destroy Country X).

With this last puzzle piece in place, the new hierarchy of fictions of Country X, complete with a strong Constitution, a liberal democratic government, a unifying monarchy, a powerful set of foundational myths, a proud and ambitious people, and a culture that emphasises strength, unity, liberty, innovation, and wealth creation, stabilises.

Conclusion

I think that social engineering, when done for the good of mankind, is a noble pursuit. The Lutherans in Germany, for instance, were Vindanists who sought to redraw the hierarchy of fictions that made up Christianity by ridding it of those fictions that enabled the Catholic Church’s perceived abuses and errors and reducing it to the five solae. Nelson Mandela and the ANC were Vindanists who toppled the apartheid hierarchy in South Africa and the office of the American SCAP were Vindanists who fundamentally edited the hierarchy of the Japanese Empire after the Second World War. Interestingly, it was religious ontology that inspired me to write this essay, such as this video on YouTube that made me ponder how many humans seem to need unquestionable fictional foundations—gods—for their societies, and how oftentimes, even where these gods have long gone silent, it is still them who are truly holding everything together. However, it is only once the wisest of these humans metaphilosophise and recognise their fictions as fictions that they can begin to bring about change in their social structures. Relative to other animals our size, humans aren’t very strong, very fast, or very sturdy at all; it is in their numbers where their strength lies—because these numbers are what exponentiate their cognitive ability and enable them to allocate massive amounts of resources.

Say that in two different parallel universes, you observe a street in India on which an injured, one-month-old pup is about to bleed to death and can only be saved if someone gets it to a vet immediately. In both universes, two Hindu men are at the side of the street, looking at the dog, but the hierarchy of fictions that makes up institutional Hinduism is different in either universe. In the first universe, Hinduism is Smritist, traditionalist, and dogmatic:

Every consequence incurred by a being is the result of their karma, either in this present life or in one or more of the past lives.

The first man is utterly unempathetic to the dying pup, declaring in his head, “It must have sinned in some past life; it deserves this.” He feels nothing for the pup. The second man is stuck in a moral battle—on one hand, he feels sad for the pup and his conscience is pushing him to go and help it, but on the other, his Smritist beliefs are telling him that it is not really his place to intervene because the pup must surely have sinned in some past life and this suffering is therefore deserved. He is late for work, so he folds to the latter inclination. The pup continues to suffer alone and dies.

In the second universe, Hinduism used to be Smritist, traditionalist, and dogmatic, but then Vindanist statesmen led a powerful, countrywide Vedic revival movement, using a Reinterpretation Edict like Country X did to selectively reject Smriti scripture that does not align with the Vedic constitution and with modern values and ideals, eventually leading to an evolved, grassroots, and purist form of Hinduism that is Shrutist, universalist, secular, and liberal: